Chicago and the Great Migration

Introduction

"When the Emancipation Proclamation was signed less than 8 percent of the African-American population lived in the Northeast or Midwest. Even by 1900, approximately 90 percent of all African- Americans still resided in the South. However, migration from the South has long been a significant feature of black history. An early exodus from the South occurred between 1879 and 1881, when about 60,000 African-Americans moved into Kansas and others settled in the Oklahoma Indian Territories in search of social and economic freedom.

Between 1915 and 1970, six million African Americans left their homes in the South and moved to states in the North and West.

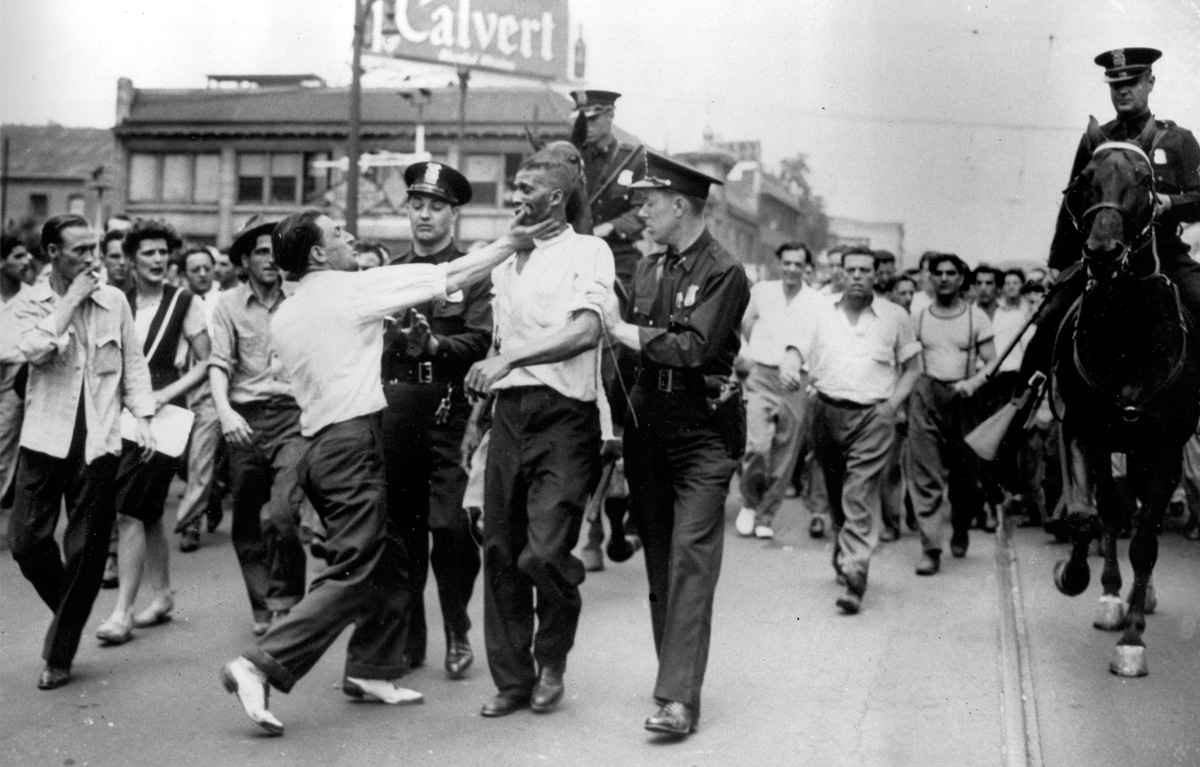

In the early decades of the twentieth century, movement of blacks to the North increased tremendously. The reasons for this "Great Migration," as it came to be called, are complex. Thousands of African-Americans left the South to escape sharecropping, worsening economic conditions, and the lynch mob. They sought higher wages, better homes, and political rights. Between 1940 and 1970 continued migration transformed the country's African-American population from a predominately southern, rural group to a northern, urban one.

The movement of African-Americans within the United States continues today. Further research in the Library's general and special collections could help assess how migration affected social and economic changes in individual cities, towns, neighborhoods, and even families." (from Library of Congress)

The Second Great Migration

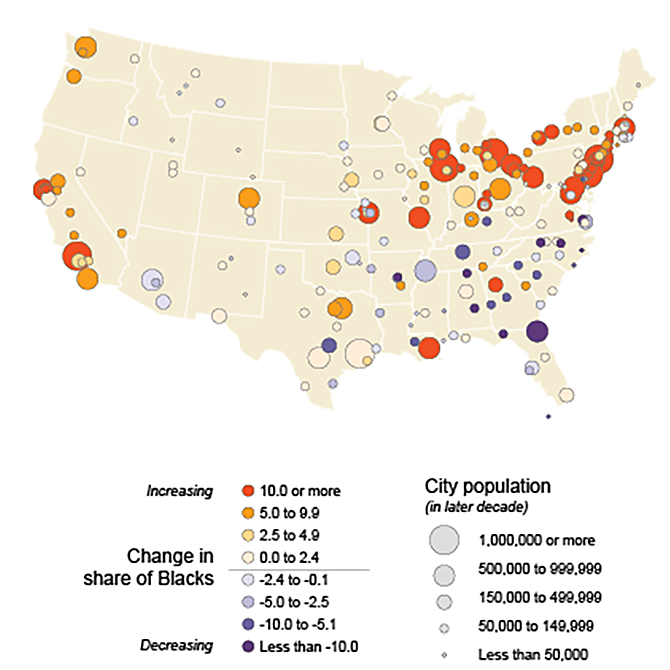

In the early 20th century, strict legislation limited immigration into the U.S. and brought about a shortage of labor in many industrial and manufacturing centers in the Northeast and Midwest. These cities became common destinations for Black migrants from the South. Cities that experienced substantial changes in racial composition between 1910 and 1940 include Chicago, Detroit, New York City, and Philadelphia.

During and after WWII, Black migrants flooded into many of the cities that were destinations before the war, following friends and relatives that had made the journey earlier. Poor economic conditions in the Jim Crow South spurred a larger migration flow than was the case in the 1910-to-1940 period and resulted in the creation of large Black population centers in many cities across the Northeast, Midwest, and West.

Ebb and Flow

"Migration ebbed and flowed for six decades, accelerating rapidly in the 1940s and 1950s. The expansion of industry during World War II again provided the stimulus. This time, however, the invention of the mechanical cotton picker toward the end of the 1940s provided a push from the South that outlasted the expansion of Chicago's job market. By the 1960s Chicago's packinghouses had closed and its steel mills were beginning to decline.

What had once been envisioned as a “Promised Land” for anyone willing to work hard now offered opportunities mainly to educated men and women.

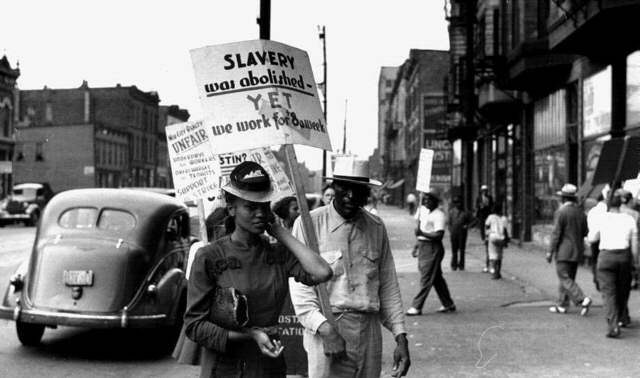

The Great Migration established the foundation of Chicago's African American industrial working class. Despite the tensions between newcomers and “old settlers,” related to differences in age, region of origin, and class, the Great Migration established the foundation for black political power, business enterprise, and union activism." (Grossman)

Cultural Impacts

"The Great Migration established the foundation of Chicago's African American industrial working class. Despite the tensions between newcomers and “old settlers,” related to differences in age, region of origin, and class, the Great Migration established the foundation for black political power, business enterprise, and union activism."

"The Great Migration's impact on cultural life in Chicago is most evident in the southern influence on the Chicago Renaissance of the 1930s and 1940s, as well as blues music, cuisine, churches, and the numerous family and community associations that link Chicago with its southern hinterland—especially Mississippi.

To many black Chicagoans the South remains “home,” and by the late 1980s increasing evidence of significant reverse migration, especially among retired people, began to appear."

Bibliography

Grossman, James R. “Great Migration.” Encyclopedia of Chicago. University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Grossman, James R. Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners and the Great Migration. University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Lemann, Nicholas. The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How it Changed America. Knopf, 1991.

Trotter, Joe W. Jr. “Migration: U.S. Migration/Population.” Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History. Thomson Gale, 2006.