St. John the Baptist Pilgrim Badge

Introduction

Amiens Cathedral located in Amiens, France a city whose patron saint is John the Baptist, drew many pilgrims who later purchased the John the Baptist pilgrim badge. Pilgrims in the Middle Ages often remembered their journey with a small metal badge. These pilgrim badges represented the holy site and were believed to hold sacred power, often used for medicinal and spiritual purposes, as well as functioning as souvenirs [1].

The pilgrimage badge of St. John the Baptist, sometimes referred to as the Amiens badge, features the head of John the Baptist on a plate in the center, a reference to the saint’s death by beheading. The badge is made of lead alloy and is 42 millimeters in diameter, about the diameter of the top of a soda can. On both sides of the head of John the Baptist is a figure with a candle in hand. This imagery is surrounded by a ring containing the inscription “behold the sign of the face of John the Baptist” [2]. In addition, there are loops on the top right of the round badge and two on the bottom. These loops would likely be used by pilgrims to attach the object to a hat, coat, or bag as they made their pilgrimage.

Behold the sign of the face of John the Baptist

While this object was an object of devotion and beauty, it was also practical. From the Amiens badge we can begin to understand the significance of material objects in the Middle Ages. This artifact demonstrates the ingenuity and ability of those living in the medieval period to develop such an object. In addition, one can begin to understand the importance of religion in daily life for the average person living in Medieval Europe.

St. John the Baptist in Amiens

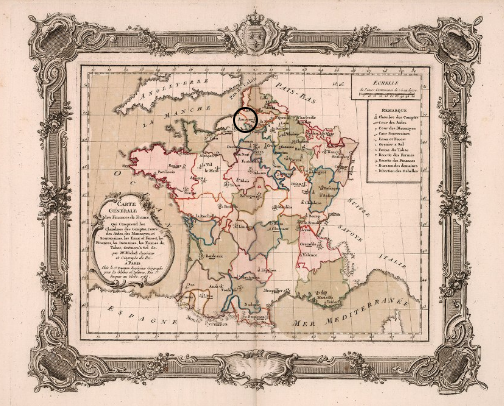

We can learn about the importance of religious life and pilgrimage in the medieval period through this 13th century pilgrimage badge. St. John the Baptist is the patron saint of Amiens, a town in northern France. In 1206, after the sack of Constantinople, William de Walon acquired a relic of John the Baptist’s skull and brought it to Amiens [3]. According to biblical accounts, King Herod's daughter ordered the beheading of John the Baptist and asked that his head be placed on a platter. Pilgrims in the medieval period traveled to Amiens Cathedral to show their devotion and see the remains of the saint’s skull kept in the Cathedral.

The pilgrimage badge depicting John the Baptist's severed head not only represents a pilgrim's devotion after completing a pilgrimage, but the badge itself contained significance. Once the pilgrim reached the holy site, the badge was considered sacred and could be given to family members or worn in order to carry the power of the saint with the owner [4].

In the Middle Ages, worshippers treated saints with reverence and often expressed devotion to a saint through pilgrimage. Throughout medieval society, following the cult of saints became a popular form of worship. The cult of saints refers to the significance of the saint’s name, the treatment of its bodily remains, and the reverence for a saint in writing [5]. In the case of St. John the Baptist, for example, one can see this type of reverence for a holy person. Medieval Christians were likely familiar with the story of John the Baptist and traveled to Amiens, France in order to express their devotion to the saint by visiting the place where the remains of the saint’s skulls are kept, while, of course, understanding which saint is referenced with the name “St. John the Baptist.”

The pilgrimage badge depicting John the Baptist's severed head not only represents a pilgrim's devotion after completing a pilgrimage, but the badge itself contained significance.

Saints’ bodies were often believed to be incorrupt, that is, they did not experience natural decay [6]. Worshippers visited these bodies of saints in order to experience their healing power. However, even the parts of the body of a saint, such as the skull of John the Baptist, were believed to hold the same power as an entire body. Pilgrims traveled great distances in order to be healed while showing reverence for these sacred bodies [7].

Creating the Badge

The production process allowed pilgrim badges to be produced quickly and in large quantities. Artisans made a design in reference to a specific saint, relic, or holy place and carved a mold of the design into limestone. After the mold was created, metal was then cast into the mold to create a badge with an image [8]. Secular badges were also popular at the time, and included comedic designs. The St. John the Baptist badge used intricate detail, such as the scripture circling the border. Artisans often had workshops in their own homes and some shrines had private workshops for the creation of their particular badges. Inexpensive and lightweight materials such as lead and tin allowed pilgrims to wear and carry the badges with minimal effort [9].

Pilgrimage in Medieval Europe

We can learn from the large amounts of pilgrim badges that have been found that pilgrimages became popular for common people as well as the wealthy. Those in the Middle Ages traveled to holy places as a sign of devotion, or for healing or leisure [10]. Once they completed their pilgrimage, many pilgrims bought a badge in order to remember their journey. These badges showed that medieval men and women were not only concerned with going on pilgrimages, but also with demonstrating to others that they were devout pilgrims. In addition to souvenirs, pilgrim badges were also considered sacred. Badges were often welded into town bells to cleanse the air and deposited into rivers, thus cleansing the water [11].

The John the Baptist badge is just one example of a medieval pilgrim badge. Its survival has allowed historians to draw conclusions about life in the Middle Ages and the importance of saints to the people of the time. Worship of the different cults of saints became popular in Medieval society due to the healing power of saints. This devout, mainly Christian society placed its faith in those the Church deemed holy and pilgrimages acted as a means to grow closer to those sacred people in this lifetime. Although pilgrim badges began as a symbol of wealth and the ability to travel, they became a common symbol of devotion, available even to the average layperson.

Footnotes

[1] Chloe M. Pelletier, “The Pilgrim's Badge: Water, Air, and the Flow of Sacred Matter.” Postmedieval: a Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 8, no. 2 (2017): 240–53.

[2] The British Museum,“Pilgrim Badge,” British Museum, 2019, research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?from=ad&fromDate=1200&object=21074&objectId=49821&page=1&partId=1&to=ad&toDate=1400.

[3] The British Museum,“Pilgrim Badge,” British Museum, 2019, research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?from=ad&fromDate=1200&object=21074&objectId=49821&page=1&partId=1&to=ad&toDate=1400.

[4] Peter Murray Jones,"Amulets: Prescriptions and Surviving Objects from Late Medieval England," In Beyond Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges: Essays in Honour of Brian Spencer, edited by Blick Sarah, 101. (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2007). http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1cd0px1.14.

[5] Robert Bartlett, "The Nature of Cult," In Why Can the Dead Do Such Great Things?: Saints and Worshippers from the Martyrs to the Reformation, (Princeton University Press, 2013): 95, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46n3wb.9.

[6] Bartlett, 101.

[7] Bartlett, 102.

[8] Jonathan Milohnić, “Pilgrim Badge.” Medieval London. Museum of London, 2017. https://medievallondon.ace.fordham.edu/collections/show/28.

[9] Robert Bartlett, "Pilgrimage," In Why Can the Dead Do Such Great Things?: Saints and Worshippers from the Martyrs to the Reformation, (Princeton University Press, 2013): 441, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46n3wb.15.

[10] Jonathan Milohnić, “Pilgrim Badge.” Medieval London. Museum of London, 2017. https://medievallondon.ace.fordham.edu/collections/show/28.

[11] Chloe M. Pelletier, “The Pilgrim's Badge: Water, Air, and the Flow of Sacred Matter.” Postmedieval: a Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 8, no. 2 (2017): 240–53.