Clara Zetkin: The Crossroad of Socialism and Feminism

A Socialist Argument for Feminism

Clara Zetkin marks the crossroad of two socio-political movements in Germany in the late nineteenth, early twentieth centuries: socialism and feminism. While she labeled herself as a socialist first and foremost, she can also be called a feminist because of her activism for women's rights and her public role as a leader of socialist women. However, she used her socialist ideology to define her feminist goals, and her belief in women's rights came from her support of socialism in what was best for society as a whole. It is therefore important to look at her as a leader of both movements in tandem.

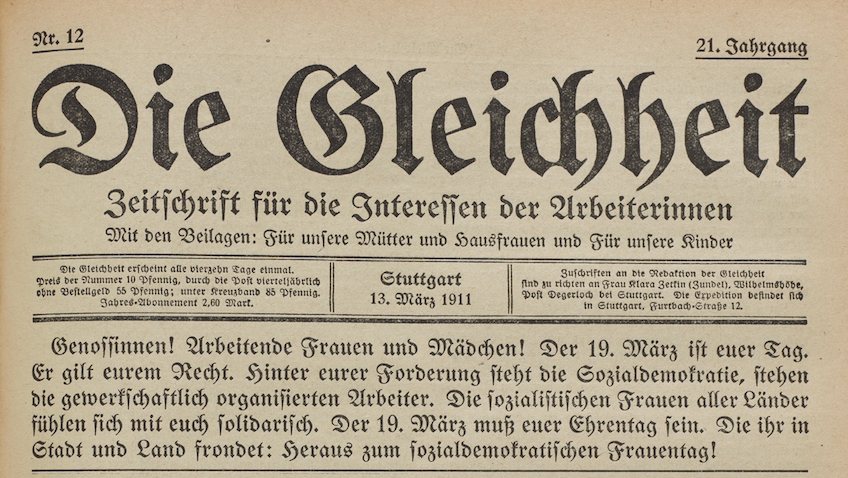

Zetkin spent much of her career as a political figure in Germany educating women to get them politically involved so that they could support the socialist cause. She was involved in trade union organization, a socialist women's magazine called Die Gleichheit (Equality), and recruiting members to the largest socialist political party in Europe at the time, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Her political standing in Germany was significant, especially given that the Law of Association banned women from political association until 1908. Zetkin also left her mark internationally with her role in founding International Women's Day. Clara Zetkin is an important figure in the history of both socialism and feminism for her devotion to the class struggle and her activism concerning women's rights.

Setting the Scene: Germany at the Time

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Germany industrialized fairly rapidly, leading to dramatic changes in the way people lived and worked.1 One such change was the rise of the bourgeoisie and proletariat due to a growing rift between the affluent and working classes. As a result, socialism gained popularity as the political ideology that favored the workers, because it questioned the capitalist and private-ownership nature of modern society, thus challenging economic domination by the minority bourgeoisie. Property ownership, in the works of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and most notably on the subject of women, August Bebel, included the claim that marriage as an institution left women economically dependent on men, essentially making them the property of men.2 Labor would afford women with economic freedom from men, but true female emancipation could only be achieved through class emancipation. That is to say, a revolution by the proletariat and the redistribution of wealth. In Germany, the SPD was influential as the largest socialist political party in Europe at this time, and it also had one of the highest female participation rates of any other socialist party.3

At the same time, the feminist movement was also underway and gaining popularity. This movement started with the “surplus women” of the bourgeoisie, women who were left unmarried because of how the Industrial Revolution had changed the trends of marriage and family life.4 Traditionally, women of this class were not expected to work outside the home. However, without husbands to support them economically, unmarried women began campaigning for equal rights with men, including women’s suffrage, education, and work. Because these women came from the upper classes, the movement came to be called bourgeois feminism. Both socialism and feminism had their appeal for working-class women, who as both women and members of the proletariat could identify with each. As a result, it was inevitable that these two movements crossed paths in Germany.

Who was Clara Zetkin

Clara Zetkin was born Clara Eissner on July 15, 1857 in a little Saxon village in Germany.5 She received a thorough education growing up, and was influenced by both her mother Josephine Eissner, an early feminist advocate, and by her teacher Auguste Schmidt, on the topic of women’s rights.6 While furthering her education in Leipzig, Zetkin encountered a group of exiled Russians that indoctrinated her on socialism, including Ossip Zetkin, with whom she became personally involved while she became politically involved with the SPD.7 When socialism was banned in Germany under the Anti-Socialist Law in 1878, Ossip and other socialists were expelled from Germany as undesirables.8 He moved to Paris and Clara soon followed him. Life in Paris was difficult and work was hard to come by. The tough living conditions took their toll on the couple and their two young kids (though Clara took the last name Zetkin, she and Ossip never married), which led to Ossip’s death in 1889. Living on the brink of poverty however strengthened Clara’s resolution to socialism, and having to support her partner as well as her children as a working woman influenced her views of women’s rights for the working class.9 She returned to Germany after the end of the ban on socialism in 1890 and settled in Stuttgart, a significant center of social-democrat publishing, to throw herself into the socialist cause.10 In her long career, Zetkin gave many speeches, attended conferences, was editor of the socialist women’s magazine Die Gleichheit from 1891 to 1917, and worked tirelessly to educate women on socialism and recruit them for the party.

Analyzing Socialism and Feminism

To better understand the political situation of Zetkin's time, there are three different approaches historians take in analyzing the intersection of feminism and socialism in Germany during the late nineteenth, early twentieth centuries.

The first approach many historians take is to view the two movements as completely separate due to the class-based ideologies of each movement. Socialism focuses on the oppression of the proletariat by the upper classes while feminism, which in this view is characterized as a distinctly middle-class initiative, focuses on the oppression of women in society. It is therefore difficult for the two ideologies to find common ground in their political aims.11 Clara Zetkin fits into this viewpoint, as many historians have stressed her devotion to socialism over women's issues and emphasized her distinction from bourgeois feminism.

The second approach historians take claims that the SPD acknowledged the feminist concerns of socialist women, but subjugated their demands in favor of wider party goals.12 Part of this subjugation had to do with the bourgeois association with the word feminism. This upper-class association made feminism unattractive to the SPD, which advertised itself as the political party of the working class.13 As a result, socialism had limited potential for achieving women's rights in Germany.

The last approach by historians argues that many socialist women were in fact “reluctant feminists” themselves, because of their conflicting gender and class loyalties.14 This conflict arose from a working woman's commitment to her class, and her commitment to her gender. Zetkin is repeatedly referred to as a reluctant feminist because while she did self-identify as a socialist, she still had feminist goals, and it is therefore difficult to categorize her as strictly one or the other. Ultimately, this viewpoint argues that to be either feminist or socialist is not mutually exclusive, and there are women who can be called both.

In the case of Clara Zetkin, she was an unusual feminist in that socialist ideology formed the basis of all her arguments in favor of women’s rights. This socialist foundation can be seen in how she viewed women and women’s issues as subordinate to socialist issues, but also in how she used socialism to justify advocating for women’s rights.

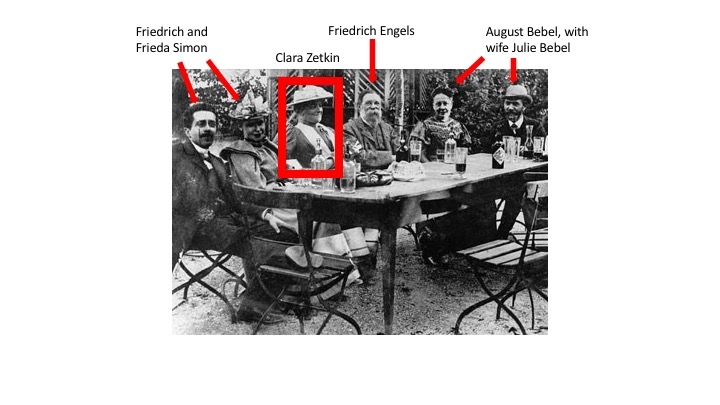

A Seat at the Table

Clara Zetkin beside fellow German delegates during a break at the International Worker's Conference in Zurich, 1893. Zetkin went to many conferences and was a prominent figure at socialist conventions. Her attendance is significant in that it shows her leadership in representing women and that she held a spot among other influential figures of German socialism, such as Bebel and Engels. (Frieda was Bebel's daughter)

Zetkin's Socialist Foundation

The proletarian woman fights hand in hand with the man of her class against capitalist society.

Zetkin in her speech "Only in Conjunction with the Proletarian Woman will Socialism be Victorious," 1896

Before delving into Zetkin's arguments in favor of women's rights, it is important to understand her political beliefs, as these formed the foundation of her arguments. Zetkin was undeniably a socialist before anything else; her primary allegiance was to the class struggle of socialism. She only concerned herself with women's issues when those concerns were justified by socialism.15 She herself saw the women's movement as an auxiliary to the socialist movement, and she refused to let the issue of gender take center stage over the socialist cause. Zetkin was clear on this point in her speech “For the Liberation of Women,” given at the International Worker’s Conference in Paris, 1889, where on behalf of working women she said “we do not want to separate our cause from that of the working class in general” because the emancipation of women could only be achieved with the “emancipation of labor from capital,” or socialism.16 She only agitated for women's right when it fit a socialist agenda.

This put Zetkin at odds with bourgeois feminists, whom she criticized for focusing too heavily on gender while she saw the greatest social injustice as class. In her 1896 speech “Only in Conjunction with the Proletarian Woman,” Zetkin proclaimed that “the proletarian woman fights hand in hand with the man of her class against capitalist society.”17 Zetkin went on to explain this statement by saying that working women had economic freedom in their labor, an argument that harkens back to Bebel's claim in his book that marriage makes women economically dependent on men because women are not earning their own wages. Thus working-class women were untied with working-class men, equal under the weight of capitalist exploitation. As proletarian women had economic equality in their labor, a claim crucial to Zetkin's later arguments in favor other equalities, they fought a different battle from bourgeois women, and Zetkin consistently emphasized the necessity of keeping the two movements separate so that their aims did not get confused.

Zetkin for Women's Rights

In claiming that proletarian men and women were already united in the fight against capitalism, it then made sense for Zetkin to use this socialist perspective to argue that for women to truly benefit the socialist cause, they needed to be “equipped with the same weapons,” as she put it in her 1896 speech, as their male counterparts: with political and legal rights.18 Armed with this rationale, Zetkin advocated for women’s rights with a purely socialist outlook. Her stance on female suffrage demonstrates her socialist reasoning. She claimed that women needed to be politically educated because in the past, they have been excluded from the political arena and left ignorant. Being able to participate in politics through voting would encourage interest and education on political matters, and as a result working-class women would naturally align themselves with socialism as the political party that addressed the needs of workers.19 The addition of female voters at the polls would then strengthen the voting power of socialists as a whole to affect change. Through this logic, women's right to vote would benefit socialism, and so Zetkin advocated for female suffrage.

Zetkin also argued for better working conditions for women. She defended female labor in her 1889 speech "For the Liberation of Women" against male opponents who feared competition. She claimed that labor was essential to the emancipation of women in affording them economic freedom, which was a step towards the emancipation of the proletariat as a whole.20 With regard to women's labor, Zetkin held a firm belief in women's roles as wives and mothers, believing it was a woman's duty to bear children that would further the cause and continue in the class struggle to overthrow capitalism.

Zetkin claimed that women therefore needed special labor laws that would allow them to fulfill this duty, so she agitated for better working conditions.21 This included protective laws for working women, eight-hour work days, laws against child labor, and for the legal and political equality of women. Zetkin was motivated by her socialist perspective, and her desire to improve the situation of working women was intended to improve the situation of the proletariat as a whole and benefit socialism more than the individual woman.

Roles in Leadership

Clara Zetkin had several important roles that demonstrated her leadership in educating and organizing women, as well as promoting their special interests.

One influential role was Zetkin's tenure as chief editor of Die Gleichheit, or Equality, from 1891 to 1917. She was offered this position by the SPD, and it made her the party's unofficial representative of women's issues within socialism. The magazine served as Zetkin's personalized guide for the education of socialist women, particularly as she wrote many of the articles herself in the first ten years of her editorship.22 The magazine also informed women on everything from factory conditions, to labor activity and strikes, to the need for female factory inspectors, as well as regularly reminded readers of the need to dissociate socialist women from bourgeois women. The magazine came to include supplements on homemaking for housewives and mothers, and on educational topics for children.23 Die Gleichheit gave Zetkin a platform from which to address issues she felt were important and her long duration as editor enhanced her influence as a leader of socialist women.

One such issue she addressed was the organization of trade unions and women's groups. These topics were not only discussed by Zetkin in Die Gleichheit, but she was also actively involved in organizing labor in trade unions and in organizing all-women groups.24 She herself was a member of the Bookbinders Union in Stuttgart, Germany, and the Tailor's and Seamstresses' Union. She traveled around Germany organizing other unions as well, giving speeches, collecting donations, and educating people on the importance of organized labor. Zetkin believed that the best way to harness the potential of the proletariat was through labor groups, as there was strength in numbers.

She took this approach for all-women groups as well, believing that women needed an environment in which to address their special interests without fear of ridicule or disregard from men, and that women were stronger when united.25 These all-women groups were also necessary for politically-involved women as the Law of Association prohibited women from association with male political groups up until 1908, when female groups were then absorbed into the SPD.

Zetkin also played an important role in the founding of International Women's Day. It was Zetkin who suggested an international holiday in honor of the fight for women's rights at an International Socialist Women Conference in Copenhagen, 1910.26 The other delegates present, for the most part, approved of the idea, and it spread world wide so that the following year saw the first celebration. International Women's Day is a holiday still celebrated today, on every March 8th, and Zetkin's role in its founding displays the international reach of her influence as a leader of socialists and a leader of women.

Final Thoughts

Clara Zetkin is a remarkable figure in history as she represents how two different socio-political movements overlapped. While she herself drew a distinction between socialism and feminism, Zetkin's political career, her ideologies, and her efforts demonstrate the potential of socialism and feminism in a combined effort to affect change in Germany during her time. Given both her commitment to socialism and her activism for women's rights, it seems appropriate to call Clara Zetkin a "reluctant feminist," even if she might have disputed such a label for herself.

Today, we as a society face both similar and different struggles than Zetkin confronted in her time. But her unusual combination of two socio-political movements to support her arguments serves as a reminder of the potential behind this kind of mixing and matching of ideologies, and that collaboration between parties can be an effective way to reach similar goals.

Primary Sources

- Bebel, August. Woman and Socialism, 50th ed. Translated by Meta L. Stern. New York: Socialist Literature Co., 1910. Accessed September 23, 2017. Marxist.org. (link)

- Footnotes: 2

- Zetkin, Clara. Clara Zetkin: Selected Writings. Edited by Philip S. Foner. New York: International Publishers, 1984.

- Footnotes: 6, 10, 16, 17, 18, 20, 23

- Zetkin, Clara. “Social Democracy and Woman Suffrage.” 1906, Translated by Jacques Bonhomme. London: n.p., 1906. Accessed November 15, 2017. Marxist.org. (link)

Secondary Sources

- Boxer, Marilyn J. "Rethinking the Socialist Construction and International Career of the Concept ‘Bourgeois Feminism’." The American Historical Review 112, no. 1 (2007): 131-58. (link)

- Cliff, Tony. “Cara Zetkin and the German Socialist Feminist Movement.” International Socialism 2, no. 13 (1981): 29-72. Accessed October 4, 2017. Marxist.org. (link)

- Footnotes: 22, 24

- Dollard, Catherine L. “Socialism and Singleness: Clara Zetkin.” In The Surplus Woman: Unmarried in Imperial Germany, 1871-1918, 164-174. New York: Berhahn Books, 2009.

- Footnotes: 4, 8

- Evans, Richard J. “Theory and Practice in German Social Democracy 1880-1914: Clara Zetkin and the Socialist Theory of Women’s Emancipation.” History of Political Thought 3, no. 2 (1982): 285-304.

- . “German Social Democracy and Women’s Suffrage 1891-1818.” Journal of Contemporary History 15, no. 3 (1980): 533-557. (link)

- Footnotes: 3, 12, 19

- . Newsletter: European Labor and Working Class History. Review of The Emancipation of Women. The Rise and Decline of the Women's Movement in German Social Democracy 1863-1933 by Werner Thönnessen, Translated by Joris de Bres. 1975. Accessed October 26, 2017. (link)

- . “Feminism and Female Emancipation in Germany 1870-1945: Sources, Methods, and Problems of Research.” Central European History 9, no. 4 (1976): 323-351. (link)

- Footnotes: 1

- Heitlinger, Alena. “The Historical Development of European Socialist Feminism.” Catalyst 10/11 (1977): 125-151.

- Footnotes: 13

- Honeycutt, Karen. “Clara Zetkin: A Socialist Approach to the Problem of Women’s Oppression.” In European Women on the Left: Socialism, Feminism, and the Problems Faced by Political Women, 1880 to the Present, edited by Jane Slaughter and Robert Kern, 29-49. West Port: Greenwood Press, 1981.

- Footnotes: 7, 9, 15, 25

- . “Socialism and Feminism in Imperial Germany.” Signs 5, no. 1 (1979): 30-41. Accessed September 23, 2017. (link)

- Kaplan, Temma. “On the Socialist Origins of International Women’s Day.” Feminist Studies 11, no. 1 (1985): 163-171. (link)

- Footnotes: 26

- Kennedy, Marie, and Chris Tilly. "Socialism, Feminism and the Stillbirth of Socialist Feminism in Europe, 1890-1920." Science & Society 51, no. 1 (1987): 6-42. Accessed September 23, 2017. (link)

- Footnotes: 11

- Pierson, Stanley. Marxist Intellectuals and the Working-Class Mentality in Germany, 1887-1912. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993.

- Quataert, Jean H. Reluctant Feminists in German Social Democracy, 1185-1917. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979.

- Footnotes: 14

- Smith, Sharon. “Women’s Liberation: The Marxist Tradition.” International Socialist Review 93 (2014). Accessed October 4, 2017. International Socialist Review. (link)

- Thönnessen, Werner. The Emancipation of Women: The Rise and Decline of the Women’s Movement in German Social Democracy, 1863-1933. Translated by Joris de Bres. London: Pluto Press, 1973.

- Ünlüdag, Tânia. “Bourgeois Mentality and Socialist Ideology as Exemplified by Clara Zetkin’s Constructs of Femininity.” International Review of Social History 47, no. 1 (2002): 33-58. Accessed October 3, 2017, ProQuest. (link)

- Footnotes: 5, 21

Images by Order

- Unknown, Clara Zetkin. 1910, Black and White Photograph, 8.5 x 13.5 cm. Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin. Available from: LeMO, (accessed December 12, 2017). (link)

- Robert Friedrich Stieler, The BASF-chemical factories in Ludwigshafen, Germany, 1881. 1881. Postcard 7.71 x 4.33 in. Public Domain, Available from: Wikimedia Commons (accessed December 15, 2017). (link)

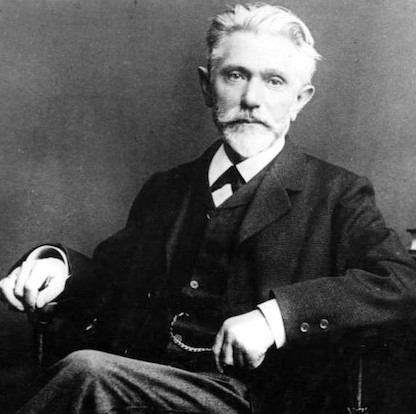

- Unknown, August Bebel. 1898, Black and White Photo, 2825x3765 pixels. Available from: Bundesarchiv, (accessed December 12, 2017). (link)

- Unknown, Clara Zetkin during a congress in Zurich 1897. 1897, Black and White Photograph, 399 x 599 pixels. From Gilbert Badia. Available from: Wikimedia Commons, (accessed December 12, 2017). (link)

- Unknown, Clara Zetkin and Rosa Luxemburg during the Congress of the Social Democratic Party, Magdeburg. c. 1911. Black and White Photograph, 6.5 x 12.38 in. Archive of Social Democracy of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Available from: AdsD, (accessed November 14, 2017). (link)

- Unknown, Clara Zetkin with Frederick Engels and August Bebel. 1895. In Clara Zetkin: Selected Writings. Edited by Philip S. Foner. Translated by Kai Schoenhals. New York: International Publishers, 1984.

- Fritz Kirchbach, Frauen!. 1919, Photograph of Poster, 8.35 x 11.11 in. Archive of Social Democracy of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Available from: AdsD, (accessed December 13, 2017). (link)

- Robert Diedrichs, Sheet 4 from the Clara Zetkin cycle 1960. 1960, Photograph of Artwork, 22.22 x 13.78 in. Public Domain, Available from: Wikimedia Commons, (accessed December 13, 2017). (link)

- Unknown, Die Gleichheit. 1911, Photograph of Newspaper, 17.78 x 10 in. Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin. Available from: LeMO, (accessed December 13, 2017). (link)

- Karl Maria Stadler, Frauentag 1914. 1914, Scan from Book, 6.21 x 4 in. Public Domain, Available from: Wikimedia Commons, (accessed December 13, 2017). (link)